Cavalier Ziliani, lei ha scelto di far pa-

gare ai figli delle quote dell’azienda

invece che cederle gratuitamente. Ci

spiega il senso?

“È una scelta che è nata, nei primi pen-

sieri, sei-sette-otto anni fa. Avevo già 75

anni. Avevo già introdotto i miei figli in

azienda, facendo loro pervenire delle

azioni. Allora non avevo il 100%, tra le

mie e quelle dei miei figli possedevamo

circa il 52% delle quote. Quando ho de-

ciso di passare la mano ho pensato che

se loro tre si fossero divisi quella per-

centuale e avessero dovuto convivere

con altri soci, sarebbe stato difficile che

andassero d’accordo. Sono riuscito a ot-

tenere dagli azionisti di allora un’opzio-

ne di acquisto, che ho tenuto in vita per

ben due anni, poi l’ho fatta scattare. A

quel punto mi sono detto che era ora di

cedere tutto ai figli. Ma ho anche pen-

sato che non dovessero avere tutto in

regalo. Questa parte aggiuntiva la do-

vevano pagare”.

Con una provocazione il gesto si po-

trebbe definire da protestante, più che

da cattolico: la responsabilità indivi-

duale che prevale sul familismo amo-

rale.

“È una riflessione che non avevo fatto

ma che condivido. Ho anche imparato da

studente, che le società di capitali sono

società di interesse pubblico: la società

“So I teachmy children:

buy the company

and not inherit it”

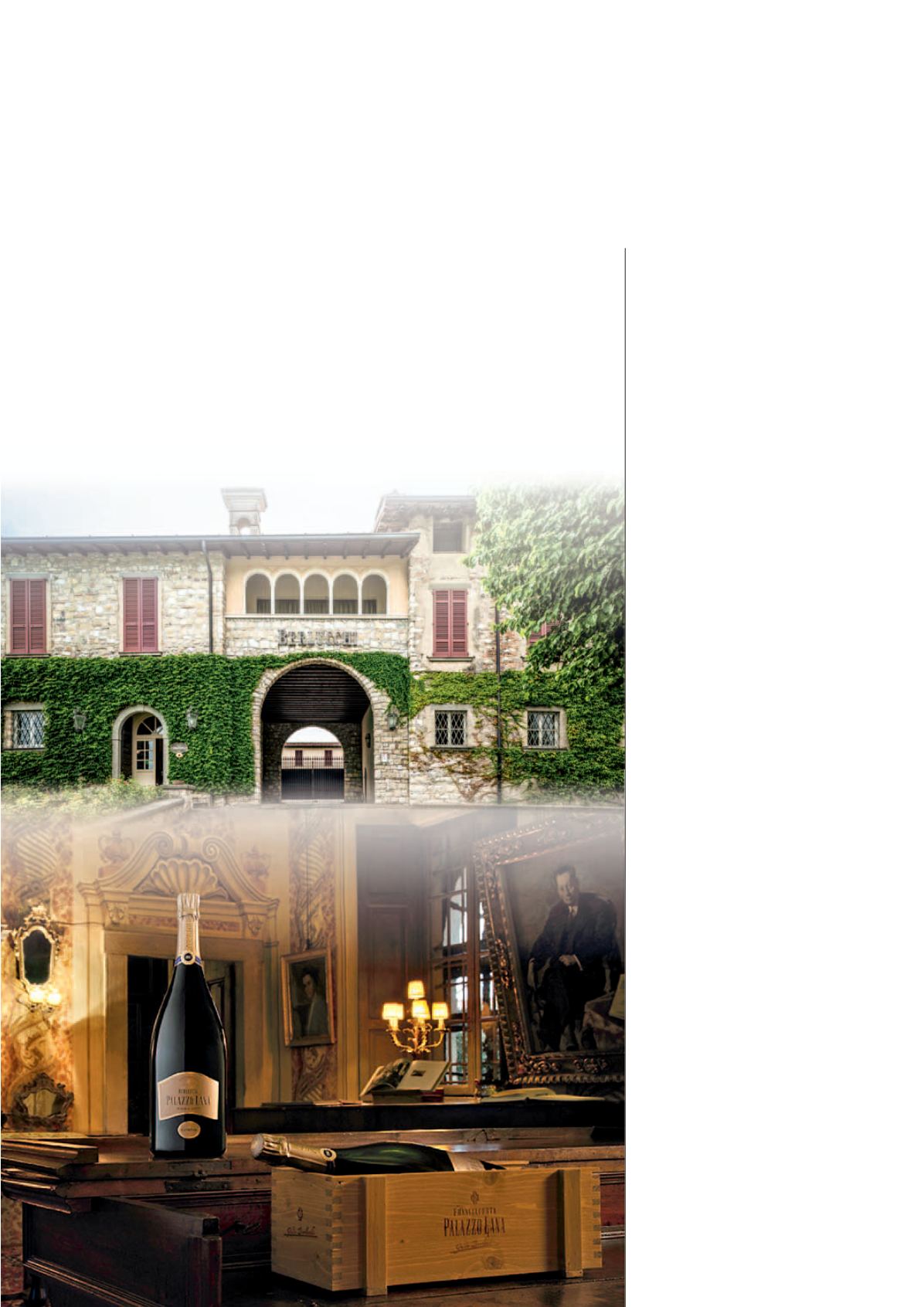

The Franciacorta aswe know it todaywould

not exist without FrancoZiliani. Today the

area south of Lake Iseo (Brescia) is known

around theworld for its sparklingwinesmade

with the ‘classicmethod’, borrowedfromthe

methodused to produce champagne. Upuntil

1961 there existednothing like it. Inbetween

all this, therewas an encounter betweena

youngwinemaker, FrancoZiliani, andGuido

Berlucchi, owner of vineyards in the area. It

was 1955and it took six years of attempts

andmistakes to get to the first production.

When the desired result was reached, success

was immediate. Ziliani tells us the details of

themeeting, at Rovato’s livestockmarket,

with “the young elegantman inwhite gloves”.

He adds that the breakthrough, for the entire

productionarea, took placewhena reporter in

the early 1970swent to seeBerlucchi’s financial

statements: the numberswere so extraordinary

that a race began towinemaking according

to the newFrenchmethod. Ziliani tells about

his transitionfrombusinessman to technician,

whichhappened very soon, with the entrance

as a shareholder in the company, because “in

my soul I have always beenan entrepreneur.”

He recalls the years as a reference brandat

the national level, followedbyEuropeanand

thenworldwide level. But he does not give up

onhis intellectual honestywhenhe recognizes

that “certain champagneswill always be

unattainable” and reflects on somemistakes

made, suchas excessive exposure in the large-

scale distribution.The interview, in the splendid

historical site of Corte Franca (Brescia), is an

opportunity to explain in-depth the choice,

unique in the Italian landscape, to sell the

company’s shares to their children instead

of simply handing themover.The children,

they say, were initially surprised, but later

appreciated it because they understood the

meaning: to give themgreater authority in the

eyes of external parties.

(Foto Antonio Saba)